Sea skaters are a super source of inspiration

A study of marine Halobates species highlights how their waterproofing techniques, size and acceleration capability helped them colonize the ocean.

Tiny sea skaters, as insect ocean pioneers, may hold the secret to developing improved water-repellant materials. A KAUST study also provides insights into the insect’s physical features, including the hairs and waxy coating that cover its body,

and its movement to evade the sea’s dangers.

“Our multidisciplinary study is the first of its kind to investigate two marine skater species, the ocean-dwelling

Halobates germanus, and a coastal relative,

H. hayanus,” says Gauri Mahadik at the

Red Sea Research Center, who worked on the study with colleagues, under the supervision of

Himanshu Mishra,

Carlos Duarte and

Sigurdur Thoroddsen. “We wanted to understand how these insects had evolved to survive in harsh marine environments where others failed.”

Faced with crashing waves, ultraviolet radiation, rain, salt water, and predatory birds and fish, insects need a specialized set of adaptations to survive in the ocean. The team captured the two Halobates species from the Red Sea and coastal mangrove

lagoons at KAUST and acclimatized them to an aquarium environment.

“It is difficult to keep marine Halobates in the lab, and there was considerable trial and error before we got it right,” says Mahadik. “These insects are cannibalistic, so it was important to keep them well fed. We spent hours trying to capture their natural behaviors on film because they jump around a lot.”

The researchers used high-resolution imaging equipment, including electron microscopy and ultrafast videography, to study the insects’ varied body hairs, grooming behavior and movements as they evaded simulated rain drops and predators. The insect’s body is covered in hairs of different shapes, lengths and diameters, and it secretes a highly water-repellant waxy cocktail that it uses to groom itself.

“The tiniest hairs are shaped like golf clubs and are packed tightly to prevent water from entering between them. This hairy layer, if the insect is submerged accidentally, encases it in an air bubble, helping it to breathe and resurface quickly”, says co-author Lanna Cheng, from Scripps Institution of Oceanography at the University of California, San Diego.

“In its resting state, not even five percent of the insect’s total leg surface is in contact with the water; so it is practically hovering on air.” says Mishra.

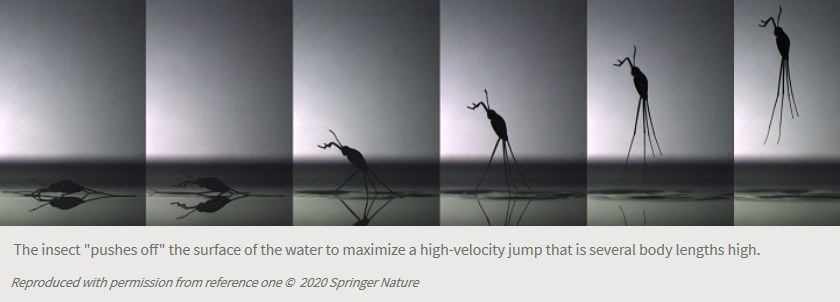

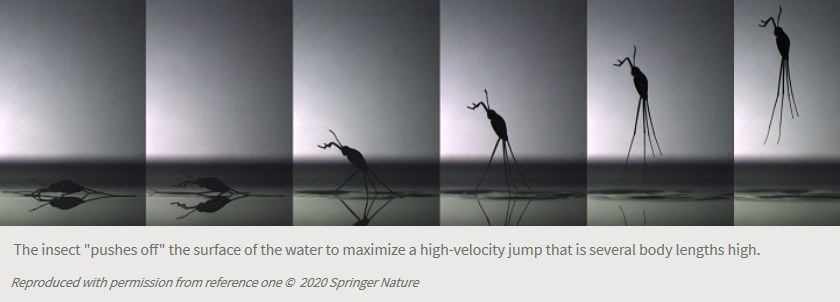

If water droplets land on the creature they roll off or, as the KAUST team caught on camera, the insect jumps and somersaults to shed the drops. The researchers were surprised by how fast it moved to evade predators and incoming waves.

“While taking off from the water surface, we observed H. germanus accelerate at around 400 m/s2,” says Thoroddsen. “Compare this with a cheetah or Usain Bolt, whose top accelerations taper off at 13 m/s2 and 3 m/s2, respectively. This extraordinary acceleration is due to the insect’s tiny size and the way it presses down on the water surface, rather like using a trampoline, to boost its jump.”

The wax secreted by the insect is of great interest to the team’s materials scientists, who are exploring new approaches for liquid-repellent technologies. The insect’s hair structures are also informing the design of new materials.

“Inspired by the mushroom-shaped hairs of Halobates, my group is developing greener and low-cost technologies for reducing frictional drag and membrane fouling,” says Mishra.