05 November, 2017

Warm and salty wastewater is a by-product of many industries, including oil and gas production, seafood processing and textile

Warm and salty wastewater is a by-product of many industries, including oil and gas production, seafood processing and textile  dyeing. KAUST researchers are exploring ways to detoxify such wastewater while simultaneously generating electricity. They are using bacteria with remarkable properties: the ability to transfer electrons outside their cells (exoelectrogenes) and the capacity to withstand extremes of temperature and salinity (extremophiles).

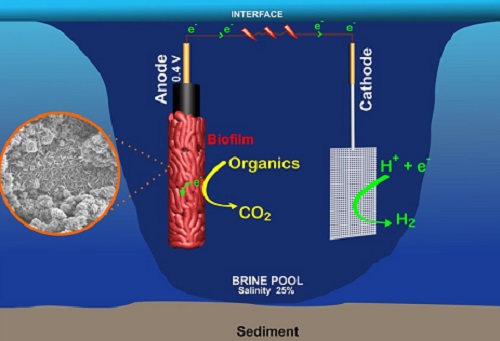

dyeing. KAUST researchers are exploring ways to detoxify such wastewater while simultaneously generating electricity. They are using bacteria with remarkable properties: the ability to transfer electrons outside their cells (exoelectrogenes) and the capacity to withstand extremes of temperature and salinity (extremophiles).The researchers, led by Pascal Saikaly, used water collected from three deep-water brine pools in the Red Sea to fill prototype microbial electrolysis cells (MECs), also known as fuel cells. “The Red Sea brine pools are good places to find extremophilic bacteria because they are among the world’s most extreme natural environments, with salinity up to 25% and temperatures higher than 46°C,” explains lead author and former Ph.D. student and postdoc of KAUST, Noura Shehab. “However, their potential for electricity generation has not previously been explored.”

Typically, MECs take the form of glass bottles, which are filled with wastewater, and contain sterile graphite and stainless-steel electrodes. “Any exoelectrogenic bacteria present can oxidize organic matter in the wastewater, generating electrons that are transported to the positive electrode. When a small voltage is applied to the system, the electrons combine with protons in the water at the negative electrode, producing hydrogen gas,” explains coauthor Krishna Katuri. Thus, they simultaneously clean the water and generate hydrogen, a clean, transportable fuel.

In this study, MECs with water from one brine pool, Valdivia, generated a stable electric current for almost two months, withstanding temperatures of 70°C and 25% salinity. Genetic analysis of the biofilm of microorganisms colonizing the anode showed a high proportion of the genus Bacterioides and significantly more of these bacteria than were found in the original samples. This enrichment of the biofilm by Bacterioides shows that members of this genus have strong potential to thrive under extreme conditions, while generating electric current.

Now a chief technologist in industry, Shehab is proud of this first study to explore the Red Sea brine pools as a novel source of exoelectrogenic bacteria. “We have shown not only that exoelectrogens are present in these environments, but also that they can be used to run MECs under challenging high temperature and high salinity conditions,” she says.

The researchers are now exploring ways to enrich MECs with other bacteria known as electrotrophs, which are able to consume electrons, also from the Red Sea. “These have the potential to convert waste products, such as carbon dioxide, into valuable chemical products, such as methane and acetate,” explains Saikaly.